Super Typhoon Ragasa

Scale & Intensity

Made landfall: Calayan Island (Babuyan chain, Philippines).

Winds: 215 km/h sustained, gusts up to 295 km/h.

Storm radius: ~320 km.

Category: Super Typhoon (among the most powerful).

Impact in the Philippines

Annual risk: Philippines hit by ~20 typhoons each year; poverty worsened by disaster-prone geography.

China’s Preparedness

Shenzhen: Preparing to evacuate 400,000 people from coastal & low-lying areas.

Guangdong province: Work, schools, and public transport suspended.

Cathay Pacific (Hong Kong): >500 flights cancelled, operations halted from Tuesday 6 pm → Thursday daytime.

Taiwan’s Situation

Forecast: “Extremely torrential rain” expected in east.

Evacuations underway in mountainous areas near Pingtung.

Officials fear damage similar to Typhoon Koinu (2023) → utility poles collapse, metal roofs torn off.

Broader Concerns

Regional disruption: Multiple Asian financial & industrial hubs affected.

Climate change link: Rising sea temperatures → stronger, more frequent super typhoons.

Socio-political dimension: Public protests in Philippines tied disasters to poor governance in infrastructure.

Key Takeaway

Super Typhoon Ragasa highlights:

Intensifying cyclones in Asia-Pacific due to climate change.

Vulnerability of coastal megacities (Shenzhen, Hong Kong, Manila, Taipei).

Need for resilient infrastructure, effective flood control, and coordinated evacuation systems.

What is a Cyclone?

A cyclone is a large-scale rotating storm system characterised by strong winds and heavy rainfall, caused by low-pressure areas and spiralling air movement influenced by the Earth’s rotation.

1. Types of Cyclones

Tropical Cyclone (Warm-core cyclone)

Forms over warm oceans (≥26°C), near but not directly at the equator.

Rising warm, moist air creates low pressure, drawing in cooler air that spirals upward.

Examples: Hurricanes (Atlantic), Typhoons (Western Pacific), Cyclones (Indian Ocean).

Extratropical Cyclones

Form outside the tropics, often associated with cold and warm fronts.

Driven by temperature differences between air masses, not warm ocean energy.

Polar Cyclones

Found in polar regions, formed due to frontal systems in extremely cold conditions.

2. Key Features of a Tropical Cyclone

Rotation:

Northern Hemisphere → anti-clockwise

Southern Hemisphere → clockwise

Caused by the Coriolis force (Earth’s rotation).

Eye:

Central calm region, often clear skies, very low pressure.

Surrounded by the eyewall, the zone of strongest winds (often >200 km/h) and heaviest rains.

Size:

Can be hundreds of kilometres in diameter.

3. Why not at the Equator?

Cyclones need the Coriolis force to spin.

At the equator, Coriolis effect is negligible.

Hence, cyclones form at least 5° latitude (≈500 km) away from the equator.

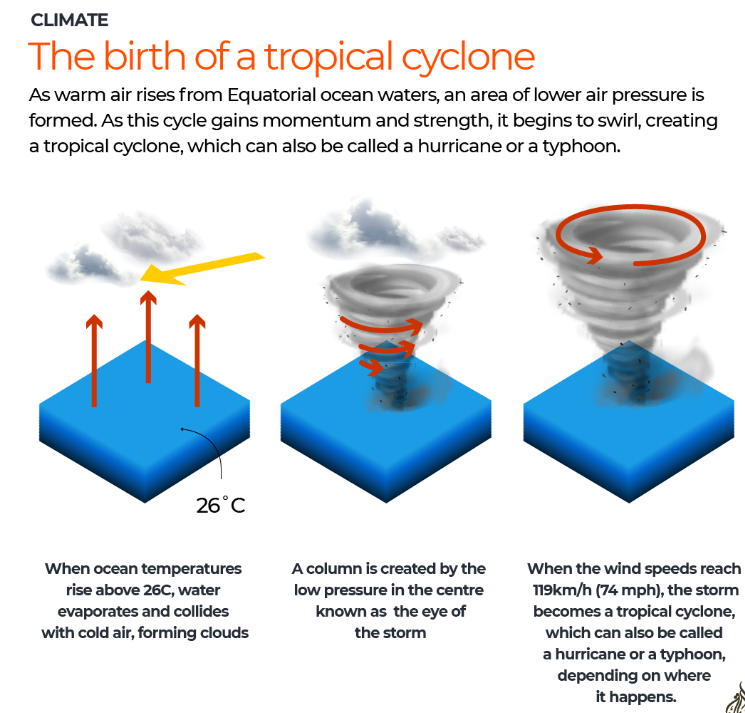

Formation of a Tropical Storm

Warm ocean waters

Tropical storms form over oceans with surface temperatures of at least 26–27°C.

Warm water heats the air above, causing it to rise rapidly.

Low pressure development

As the warm, moist air rises, it leaves behind an area of low air pressure.

Cooler air rushes in to fill this gap, which then also warms and rises.

Cyclonic circulation

This continuous cycle of rising warm air and inflow of cooler air creates strong winds and heavy rainfall.

The Coriolis effect (Earth’s rotation) causes the system to spin/rotate.

Eye formation

As rotation intensifies, a calm central zone forms called the eye.

The eye has clear skies and very low pressure, while the surrounding eyewall has the strongest winds and heaviest rain.

Storm intensification

When winds reach 63 km/h (39 mph) → it is classified as a Tropical Storm.

When winds reach 119 km/h (74 mph) → it becomes a Tropical Cyclone (called Hurricane in the Atlantic, Typhoon in the Pacific, Cyclone in the Indian Ocean).

Key Conditions Needed

Warm sea surface (≥26°C)

High humidity in lower & middle atmosphere

Low vertical wind shear (winds at different heights should not disrupt system)

At least 5° latitude away from the equator (to allow Coriolis effect to induce rotation).